Gloria Boraz

Gloria Boraz

This is the third in a series of tributes to my former teachers in America.

When I first came to the United States, I spoke nine words in English: “My name is [first/last name]” and “Where is the bathroom?”

I got along fairly well in first grade and learned hundreds more words, mostly from television, But in second grade, there was one word that seemed impossibly beyond reach to understand and enunciate: indivisible.

I belong to the glorious generation that was taught by the legendary Beverly Hills elementary school teacher, Gloria (Zemliak) Boraz. For over four decades, Mrs. Boraz taught young children everything from reading to writing and math, but she was especially known for dedicating the whole academic year to learning about the 50 American states.

For some time, many students in Mrs. Boraz’s class at Horace Mann Elementary and Middle School were middle-class Ashkenazim whose parents resided in modest homes in Beverly Hills so that they could benefit from the exemplary public schools.

Suddenly, half of Mrs. Boraz’s second grade class had unpronounceable Persian names, olive skin, dark hair, and even darker mustaches. One of those mustaches belonged to me.

But that all changed in the 1980s and early 1990s, when the Iranian revolution forced over 90% of the country’s Jews to escape and be resettled elsewhere. Suddenly, half of Mrs. Boraz’s second grade class had unpronounceable Persian names, olive skin, dark hair and even darker mustaches. One of those mustaches belonged to me.

I had spent most of first grade learning about American culture, as I wrote in an August 2022 column titled “The Teddy Bears of Redemption,” which offered gratitude to my first grade teacher, Mrs. Sadlier. But anyone who was ever blessed enough to have had Mrs. Boraz as a second grade teacher can attest that one walked out of her classroom on the last day of school with an encyclopedic knowledge of U.S. geography, natural resources and state mottos, flags and birds (For those born after 1999, encyclopedias were thick, unbiased, paper-versions of search engines. And they had pretty pictures, too.).

Mrs. Boraz hung a giant map of the U.S. which took up the entire wall at the back of her classroom. At first, I struggled to understand the concept of one country, divided into 50 states. Back in Iran, I had experienced one country, with 50 different ways to prepare Persian rice.

Given that I came to the U.S. in first grade, I understood that faculty and students would be more sympathetic to my language and cultural limitations that year. But I anticipated that by second grade, a lot more would be expected of me. When I stepped into Mrs. Boraz’s class and met whom I quickly understood to be a deeply experienced educator, I knew I was right.

It wasn’t long before the class began our “states projects.” Each year, Mrs. Boraz’s second graders were assigned individual American states to research. She was inclined to assign a greater number of states to kids who were more advanced readers and writers. That explained why one brilliant peer was assigned a whopping five states: Oregon, Idaho, Rhode Island, Delaware and most coveted of all, California, plus Washington, D.C. The only reason why I remember Natalie’s states from our second grade Class of 1991 is because I still have a laminated U.S. map in the form of a placemat that Mrs. Boraz gave each of us on the last day of school.

In Iran, I had worked so hard to be at the top of my class. But in America, I was plagued by self-doubt on every level, including academically. In my mind, I was still a high-achieving student, but I recoiled at how my teachers and peers may have perceived me.

That’s why it meant the world to me when Mrs. Boraz assigned me three wonderful, validating states: Alaska, South Dakota and Tennessee. She gave each student a set of topics to research about our states, and I happily ran to the library and begged our beloved librarian, Mrs. Marshak, who has since passed, to help me find the “A,” “S” and “T” volumes of the encyclopedia.

To this day, I still have a soft spot for those states, none of which I’ve had time to visit.

I still remember Alaska’s nickname, capital and state flower: The Last Frontier, Juneau and forget-me-not. I didn’t understand why anyone would name a flower “forget-me-not”; it seemed like too much pressure to put on a person or a flower.

I also remember South Dakota’s capital, state bird and most famous national monument: Pierre, the ring-necked pheasant and Mount Rushmore. I wondered why the capital sounded French (thanks to Alliance Israélite Universelle schools in Iran, both my mother and grandmother had taught me a little French). When I saw my first glimpse of Mount Rushmore in the encyclopedia, I was so impressed by the Americans and their sculpting prowess. The heads of those presidents on all that granite seemed much more expensive than the face of Ayatollah Khomeini that was plastered on cheap posters and billboards back in Tehran.

Tennessee brought me particular joy because I knew that if I could spell that treacherous word, I had truly learned how to read in English. Thanks to Mrs. Boraz, I was able to learn a little about Nashville and Memphis, and my love for rock ‘n’ roll has never waned.

Tennessee brought me particular joy because I knew that if I could spell that treacherous word, I had truly learned how to read in English. Thanks to Mrs. Boraz, I was able to learn a little about Nashville and Memphis, and my love for rock ‘n’ roll has never waned.

For me, Mrs. Boraz was a unique educator for two reasons: She was caring, but not overly permissive, and, being in her early 60s, she was a little older than some of the other teachers. Back then, being an older teacher wasn’t a liability; in the eyes of 30 little second graders, it made you a trusted, dare I say even definitive, expert.

In hindsight, that entire year was dedicated to all things America. We even began each morning with a series of songs about this country, all of which I learned in a few weeks. I’m referring not only to the national anthem, but also to a host of other songs, including “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.” Can you guess if I understood what “tis of thee” meant? I think we both know the answer. And “Indivisible” evaded me whenever it was time to recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

Amazingly, Mrs. Boraz accompanied each song by playing an autoharp, also known as a chord zither. Back then, I didn’t know what an autoharp was. But it was magical because Mrs. Boraz was playing it.

She gave each student an old cigar box to decorate and use as a pencil box for the whole year. I always wondered from where she secured 30 cigar boxes; she didn’t seem like much of a cigar smoker. And this was the early 1990s, when parents didn’t seem to have an issue with their kids happily using a cigar box.

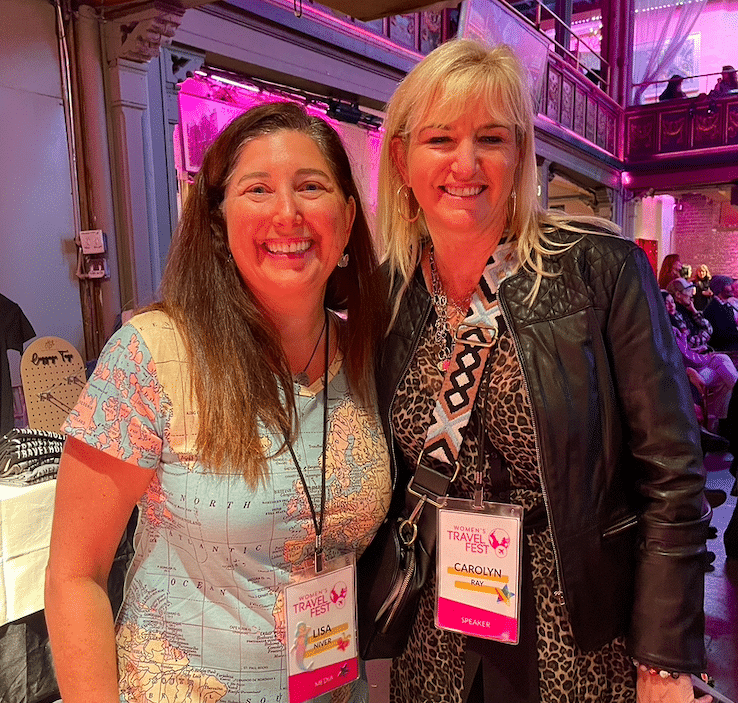

I had so many questions about my beloved Mrs. Boraz, and luckily, a few months ago, I saw a Facebook post from Horace Mann alumnus Steven Fenton that showed a selfie of him with Mrs. Boraz! Steven wrote that she was in her 90s, still living in Beverly Hills and loved connecting with former students.

I knew what I had to do. I found my three state projects, dusted them off, and, on Facebook, found one of Mrs. Boraz’s three daughters, Nancy Boraz Friedman, who had been my sixth-grade English teacher at Horace Mann.

We set up a day and time for me to visit Mrs. Boraz. I, too, would get to see her after decades, and to have my selfie with her. I planned to hold my three states in the photo, the glitter on their titles still sparkling.

But work deadlines and family commitments forced me to cancel that visit. I thought I would have more time to see Mrs. Boraz because in Steven’s Facebook post, she looked so spry and vibrant.

And then, in May, Gloria Boraz passed away.

During a phone call last week, Nancy told me that her mother “took a really bad turn very fast.” She passed away on May 21 at age 94. “She would absolutely have loved this,” Nancy said. “She would have loved that a former student would have written a column about her in the Jewish Journal.”

I held back tears as I told Nancy that I still know all 50 states and their capitals. She wasn’t surprised. “Every kid who had my mom in second grade remembers their state,” she said, then asked, “What were your states?”

Alaska, South Dakota and Tennessee.

I realize how much she impacted my love of this country. Thanks to her, I felt I knew America. And to know America is to love America.

I’ll never forgive myself for not prioritizing that visit with Mrs. Boraz. But now, I realize how much she impacted my love of this country. Thanks to her, I felt I knew America. And to know America is to love America.

All three of Mrs. Boraz’s daughters, Barbie, Leslie and Nancy became teachers, which tells you something about their mother’s love and talent for teaching. “Mom was extremely proud of that,” Nancy said, adding that her mother “loved being around children because they were honest.”

I asked her if Mrs. Boraz felt connected with being Jewish. “My mother loved being Jewish and loved not only the traditions and holidays, but also had a very strong faith in G-d,” she said. The family attended Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills and “always had Shabbat,” said Nancy. Mrs. Boraz delighted in lighting candles and preparing Shabbat every Friday night. In recent years, as she got older, Nancy always brought her challah.

When you’re a kid, it’s hard to realize that your teachers are unique individuals with their own life stories. Nancy told me that Mrs. Boraz was born in St. Louis, MO. She married Martin Boraz and the couple had Barbie, Leslie and Nancy in the same city.

The family then moved to Chicago. After some time, Martin received a job opportunity in California, in what Nancy described as a “big move” for the family. They moved to Beverly Hills to take advantage of the excellent public schools. Mrs. Boraz was a “a very active parent” at school — so active that an administrator offered to hire her if she received her teaching credentials.

Martin passed in 1984 and Mrs. Boraz was blessed with three subsequent loves: Izzy, Bob and Stan.

“Mrs. Boraz had the ability to connect with her students and she made learning fun. This combination was unique because she was dealing with seven-year-olds,” Steven told me. He was in her second grade class in 1977-78. “I think the only reason why I remember the second grade so vividly is because her presence was that large. She deftly commanded the room while also laying down the law with a smile. And she really helped me understand boundaries.”

Mrs. Boraz helped me understand boundaries, too. Maybe boundaries come with the territory when you spend nine months learning about 50 American states.

Sometimes, when I’m struggling with brain fog after a day that has depleted me mentally and physically, I cuddle close to my son as he lies asleep in bed and stare at a big map of America on the wall of his room. Some people prefer crossword puzzles or Sudoku to help keep their memory and executive functioning intact; I simply gaze at each state, its name indiscernible in the dark, and try to name each one and its capital. In an age when many Americans can’t even identify more than a few states on a map, it’s quite a feat. I still know 98 U.S. states and capitals, because I keep mixing up Concord in Vermont with Montpelier in New Hampshire.

I still deeply wish I had been able to spend time with Mrs. Boraz. But at least Nancy helped me solve another puzzle about her wonderful mother: The teachers were supposed to supply their students with pencil boxes. So each year, Mrs. Boraz visited a cigar shop on Beverly Drive and asked the owner to save her three dozen empty cigar boxes.

As for that autoharp, Nancy told me it’s still there, in Mrs. Boraz’s house.

In contemplating this column, I came to a powerful realization: Mrs. Boraz was my first introduction to learning about America in a classroom setting. I’m so blessed that, unlike many educators today, she didn’t ruin that incredibly critical experience for me by poisoning her students’ minds and hearts with a year’s worth of bashing America over its mistakes. While this is comforting to me, the thought that child refugees from around the world who arrive here today may receive their first academic introduction to America by teachers and curriculum that paint this country as unforgivably bad breaks my heart into a thousand pieces.

My love for the United States enables space for critique. But at the end of the day, that love is wholly indivisible from everything else.

See, my dear Mrs. Boraz, z”l? I finally learned the meaning of that word.

Happy Fourth of July.

Tabby Refael is an award-winning writer, speaker and weekly columnist for the Jewish Journal of greater Los Angeles. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @TabbyRefael

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.